What is it like being LGBT in Japan?

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

Social Stigmas, hardship and progress for the LGBT community in Japan

In 2018, Mio Sugita, a member of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), faced backlash after calling LGBT individuals “unproductive” as, “these men and women don’t bear children”. With comments like this from government officials, it is difficult to describe Japan as an environment where members of the LGBT community are welcome. At the same time, this incident is not wholly representative of Japan’s attitude towards the LGBT community. There are no laws that criminalize same-sex interactions between consenting adults, and there have also been promising signs of progress, as local governments, courts, and ministries take steps toward greater legal equality for LGBT individuals. According to a survey conducted by Dentsu in 2018, 78.4% of people aged 20 to 50 are in favor of same-sex marriage in Japan, leading some to describe it as a “boom” in LGBT awareness. Furthermore, there is evidence of deep cultural and historical roots in transgenderism in Japan, dating back to the Tokugawa period when transgender men affiliated with the kabuki theaters would offer sexual services to male audience members. These factors have contributed to the image of Japan as a relatively progressive nation with regard to LGBT issues in Asia. However, longstanding heteronormative views on family and marriage still make being an LGBT individual in Japan difficult.

Marriage and the Family Unit

The enduring strength of a “traditional” family unit made up of a mother, father, and child contribute to the anxiety many LGBT individuals experience when faced with the prospect of “coming out” – a term used to refer to an LGBT individuals self-disclosure regarding their sexual orientation or gender identity. A study conducted on Japanese attitudes towards sexual minorities found that the more intimate the relationship, the harder it is to be accepted; more than 40% of Japanese parents claimed it would be “unpleasant” if and when they found out their children were homosexual, while only 10% to 20% would react in a similar fashion towards a neighbor or coworker. Fears of “queering the Japanese home” deter individuals from disclosing their identity, which have given way to problematic views where “coming out” is seen as “selfish” or as a “Western concept”. Some families, while accepting of their children’s sexual identity as an LGBT individual at home, prefer that their child pretend not to be in public in order to maintain a sense of perceived normalcy.

In 2015, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe claimed that changing the Japanese constitution to allow same-sex marriage would need “extremely cautious consideration” as it “does not envisage marriage between people of the same sex”. Opinions on this interpretation are mixed. Some experts oppose this, stating that in theory, the current wording of Article 24 of the Japanese constitution would allow for same sex marriage, which is written as follows: “Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis”. Others, such as family lawyers, interpret “both sexes” to mean a man and a woman, making marriage exclusive to heterosexual individuals.

To date, same-sex marriage in Japan has not been officially legalized. Although there are municipalities that issue same-sex partnership certificates, these do not offer legal protection. This has forced some LGBT couples to think outside of the box. One study found that some gay couples in Japan use the “ordinary” (futsu) adoption system to secure their relationship by becoming parent and child – the older partner becomes the younger partner’s parent. As a family, the couple can share the same name, have mutual assistance responsibility, and secure inheritance rights. Although there are no specific numbers on how commonplace this is, anecdotal evidence suggests that it is fairly widespread.

...gay couples in Japan use the adoption system to secure their relationship by becoming parent and child... As a family, the couple can share the same name, have mutual assistance responsibility, and secure inheritance rights.

Invisible in Plain Sight

There is also a lack of political representation for LGBT individuals, rendering them “invisible”. Although some visibility may be achieved through cultural mediums such as manga, anime, and other television shows, a study on queer desire on T.V. argued that this does not equate to political presence. Furthermore, the quality of what is being made visible is also significant, as genres such as BL (Boys Love) and Yuri (Girls Love) play into preconceived fantasies of desire, where the characters are made to be particularly attractive or alluring for a heterosexual audience. There are also cases where LGBT individuals are pawned on reality T.V. shows for the sake of comic relief, thereby making what is visible a misrepresentation of the LGBT community.

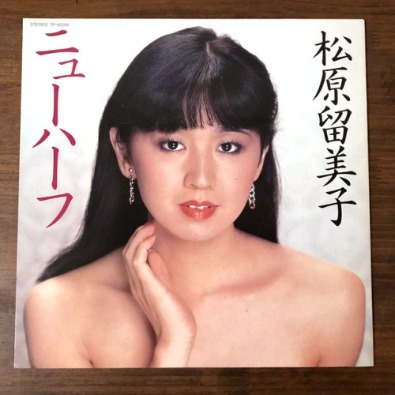

A study found that the term “nyu-hafu” (new half), which is used colloquially to refer to transgender individuals, was popularized by the media in the early 1980’s following the success of Matsubara Rumiko, a transgender model and singer who is biologically male. Not long after, in 1998, sex-change operations were legalized, leading to a widespread discusson on transexuality and transgenderism. Although this signalled a new awareness regarding the idea of gender fluidity at the time, it remains a controversial legal matter in Japan. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, transgender individuals in Japan face discrimination based on the notion that transgenderism is a mental disorder. The legal procedure to formally change one's gender is described as regressive and harmful, due to the lengthy, expensive, and irreversible medical procedures that are required of them for legal recognition.

Human Rights Watch recommends the Japanese government abolish abusive prerequisites for changing ones legal sex or gender to meet international standards put forth by the United Nations. This includes eliminating involuntary sterilization, medical surgeries and hormonal therapies, and psychosocial treatment, among others. Similarly, Amnesty International asks the Japanese government to introduce and enforce anti-discrimination legislation to protect against discrimination in all areas including sexual orientation and gender identity, among others, to ensure that LGBT individuals are not placed in a disadvantage.

Matsubara Rumiko

The current coronavirus pandemic has not made the situation much easier for members of the LGBT community in Japan. There are growing concerns among those who wish to keep their sexual orientation a secret if they happen to catch the virus, it would mean having to report the incident to their employers, which could lead to discrimination. Because same-sex couples are not officially recognized under the law, some fear exclusion from important decisionmaking processes if their partner is hospitalized due to COVID-19. As the Japanese government haphazardly put together measures to combat the coronavirus, they have failed to elaborate on who is eligible for certain programs. There have been misperceptions that same-sex parents and their children are not eligible for compensation by the government for taking a leave of absence from work, highlighting the necessity of clarifying that LGBT families are also are eligible.

Although the 2020 Tokyo Rainbow Pride parade, which celebrates diversity and LGBT rights, has been cancelled due to the coronavirus, it has since moved online, providing a platform for LGBT individuals to assemble in solidarity. The spontaneity and visibility that comes with marching through the streets become lost in an online environment, but it is still an effective way of giving voice to issues that remain undermined under Japanese law.

----------------------------------------------

About the Author

I was born and raised in America and is a recent graduate of the Global Studies program at Sophia University. In my free time I like to read novels.